The vagus nerve is like your body’s “calm button.” It connects brain and body, helps regulate stress, digestion, mood and more. When it works well, you feel safe and connected; when it’s off-balance, you may feel anxious, restless, or shut down. Polyvagal Theory explains three states of your nervous system: ventral vagal (safe & social), sympathetic (fight/flight), and dorsal vagal (shutdown). You can strengthen vagal tone through breathing, movement, social connection and everyday tools that train your body to regulate stress more easily. Let’s get into what all of this means and how it can help you.

Disclaimer: I’m not a mental health professional, everything here is shared from research and personal experience. If you’re feeling overwhelmed or need support, please consider talking to a qualified professional. You’re not alone. If you’re in the U.S., you can call or text 988 anytime. For help in other countries, visit https://findahelpline.com. Read more of our disclaimer here.

The Autonomic Nervous System and Polyvagal Theory

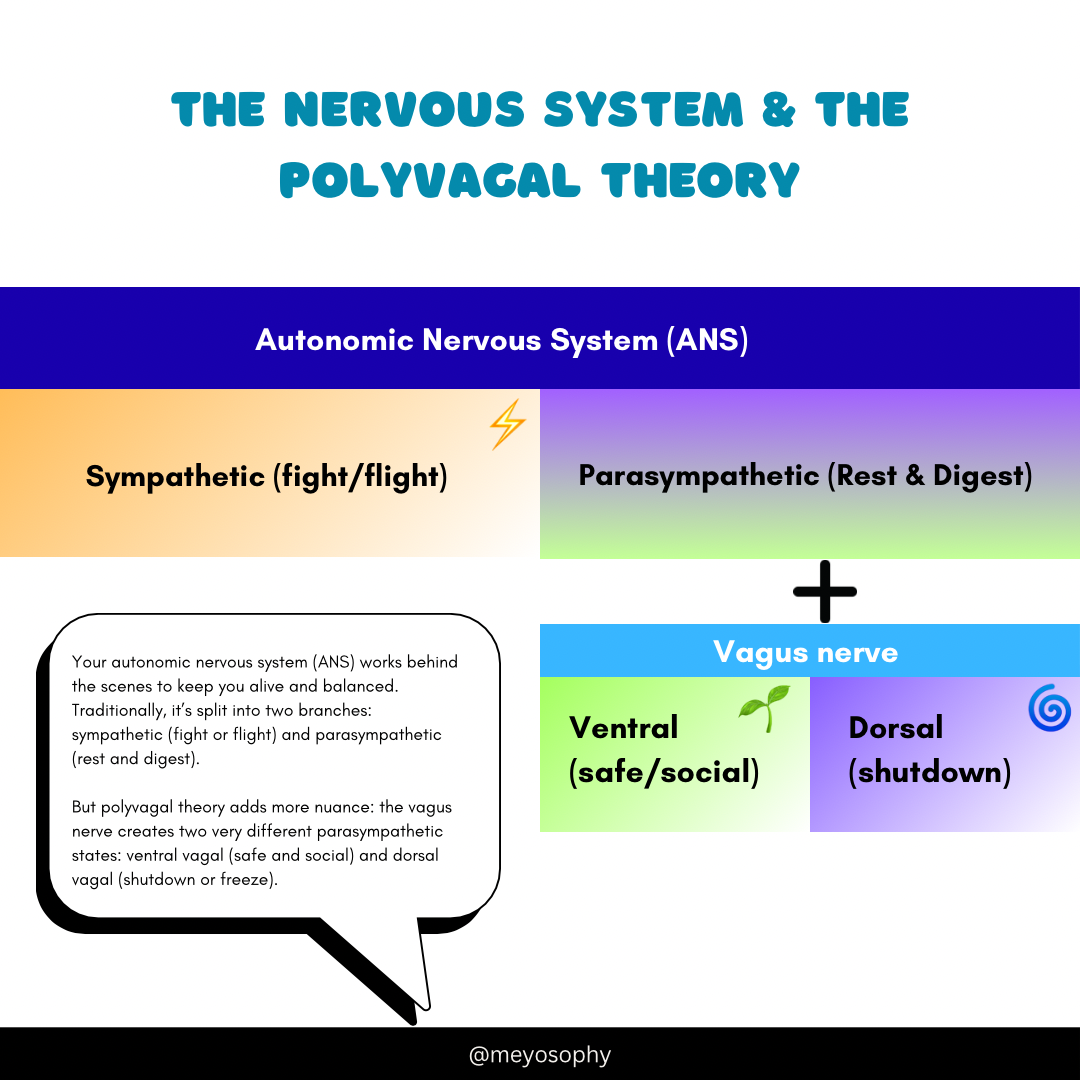

To understand why the vagus nerve matters, we first need to zoom out to the autonomic nervous system (ANS). This system runs in the background, controlling things like your heartbeat, digestion, and breathing: the stuff you don’t have to think about. Traditionally, the ANS is divided into two branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS): The accelerator. It activates fight or flight, getting you ready to respond to danger.

- Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS): The brake. It helps your body rest, digest, and return to balance.

This two-branch model explains a lot, but it doesn’t fully capture the complexity of how we actually respond to stress. That’s where Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory comes in.

Polyvagal Theory in a Nutshell

Porges suggested that the vagus nerve isn’t just one simple pathway. Instead, it has two main branches that work differently depending on whether you feel safe or threatened:

- Ventral vagal state (safety and connection): When this branch is active, you feel calm, social, and able to engage. It’s the biological foundation for feeling safe with others.

- Dorsal vagal state (shutdown and freeze): When this branch takes over under extreme stress, your body may conserve energy, go numb, or “check out.”

So instead of just fight-or-flight (sympathetic) versus rest-and-digest (parasympathetic), Polyvagal Theory introduces a third option: shutdown. This explains why some people don’t just get anxious in stressful situations, they might also feel paralyzed, disconnected, or “foggy.”

How Polyvagal Theory Builds on the ANS Model

- Traditional ANS model: Two branches (sympathetic vs. parasympathetic).

- Polyvagal Theory: Adds nuance by splitting the parasympathetic into ventral (social engagement, safety) and dorsal (shutdown).

- Key difference: The Polyvagal lens emphasizes how your nervous system continuously scans for safety (“neuroception”) and shapes not just your body’s stress response but also your ability to connect with others.

Polyvagal Theory in Therapy

Porges’ theory has inspired new approaches in psychotherapy, especially in trauma and mental health care. Therapists use it to help clients:

- Identify their current state (fight, flight, freeze, or safe/social).

- Develop tools to move back toward safety (like grounding, breathwork, or co-regulation with others). More on this later.

- Normalize reactions: instead of seeing shutdown or panic as “failures,” clients learn that these are adaptive nervous system responses.

- Create safety in therapy by focusing on cues like tone of voice, eye contact and pacing, which help engage the ventral vagal system (safety).

Therapies influenced by Polyvagal Theory include somatic experiencing, trauma-informed yoga, and body-based approaches that prioritize regulation over simply talking through problems.

In other words: it’s not just about calming down the mind, it’s about working with the nervous system as a whole.

What Is the Vagus Nerve?

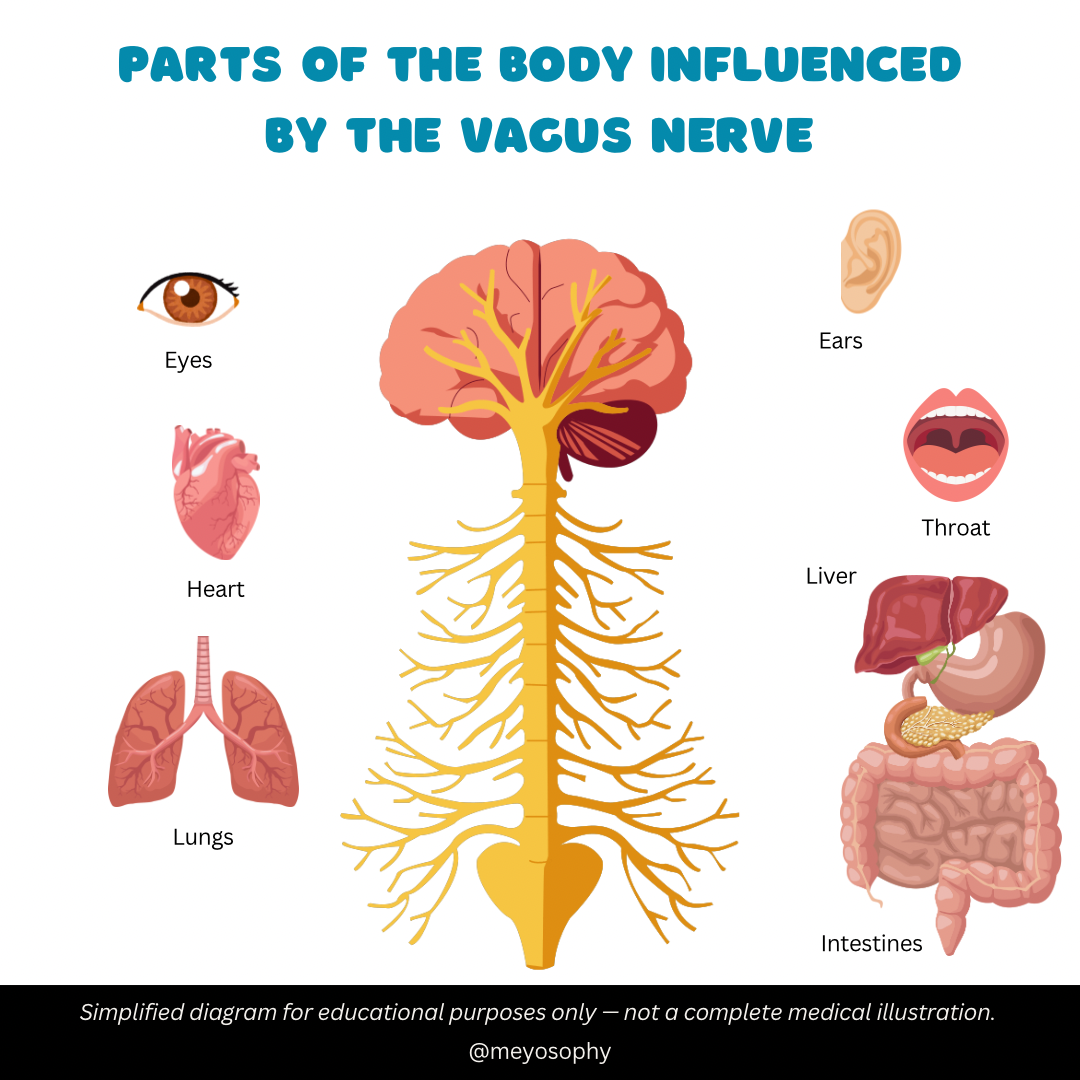

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is the longest “wandering” nerve in your body. It runs from your brainstem down through your throat, heart, lungs, and gut. Its main role? Helping your parasympathetic nervous system calm things down: slowing the heart, deepening breath, and turning on digestion[^1].

Think of it as a two-way highway:

- Upward traffic: Your organs send updates (heart rate, gut status) to your brain.

- Downward traffic: Your brain signals your organs to slow, rest, and restore.

Key jobs you’ll care about:

- Heart & lungs: Calms your heartbeat and breathing[^1].

- Gut: Promotes digestion and gut–brain communication[^2].

- Inflammation: Regulates immune and inflammatory responses[^3].

- Mood & connection: Helps you feel safe, open, and socially engaged[^4].

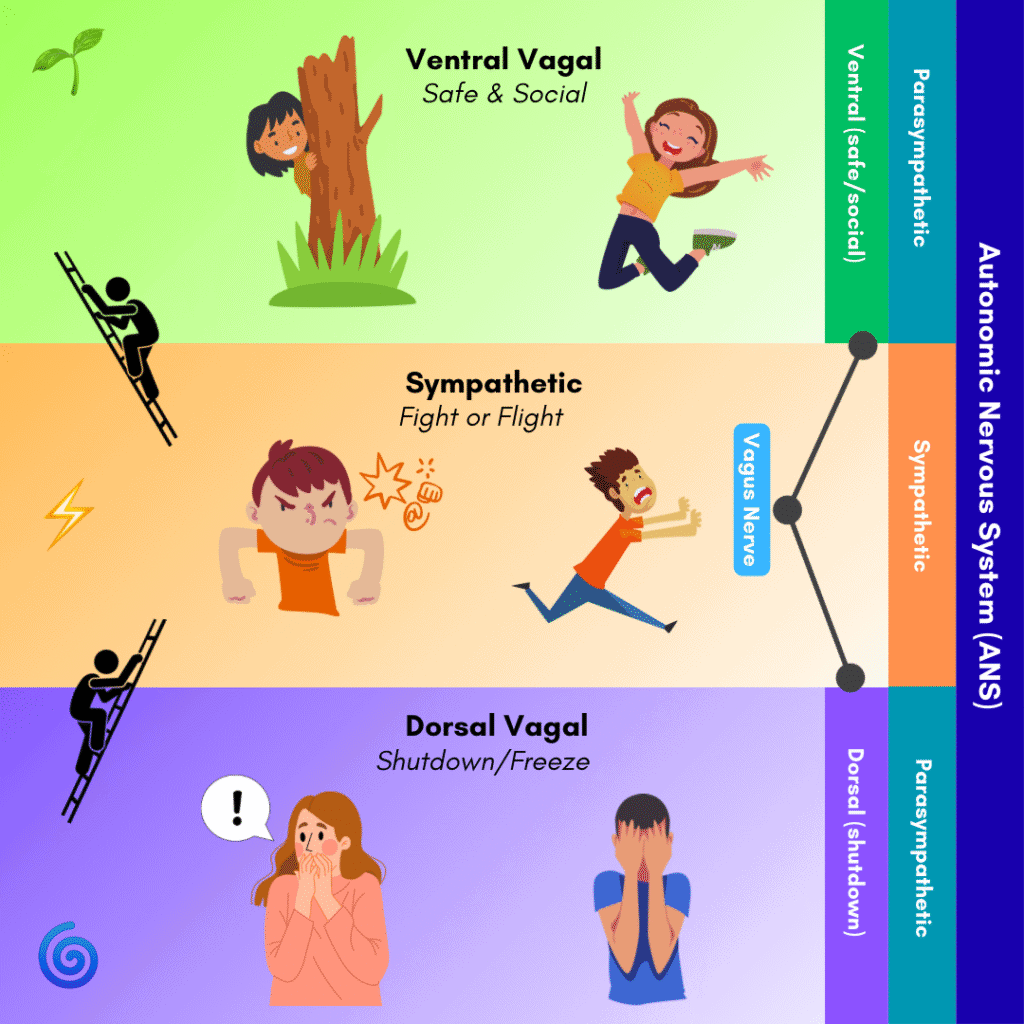

Polyvagal 101: Your Three States

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory maps how your body shifts states based on safety[^4].

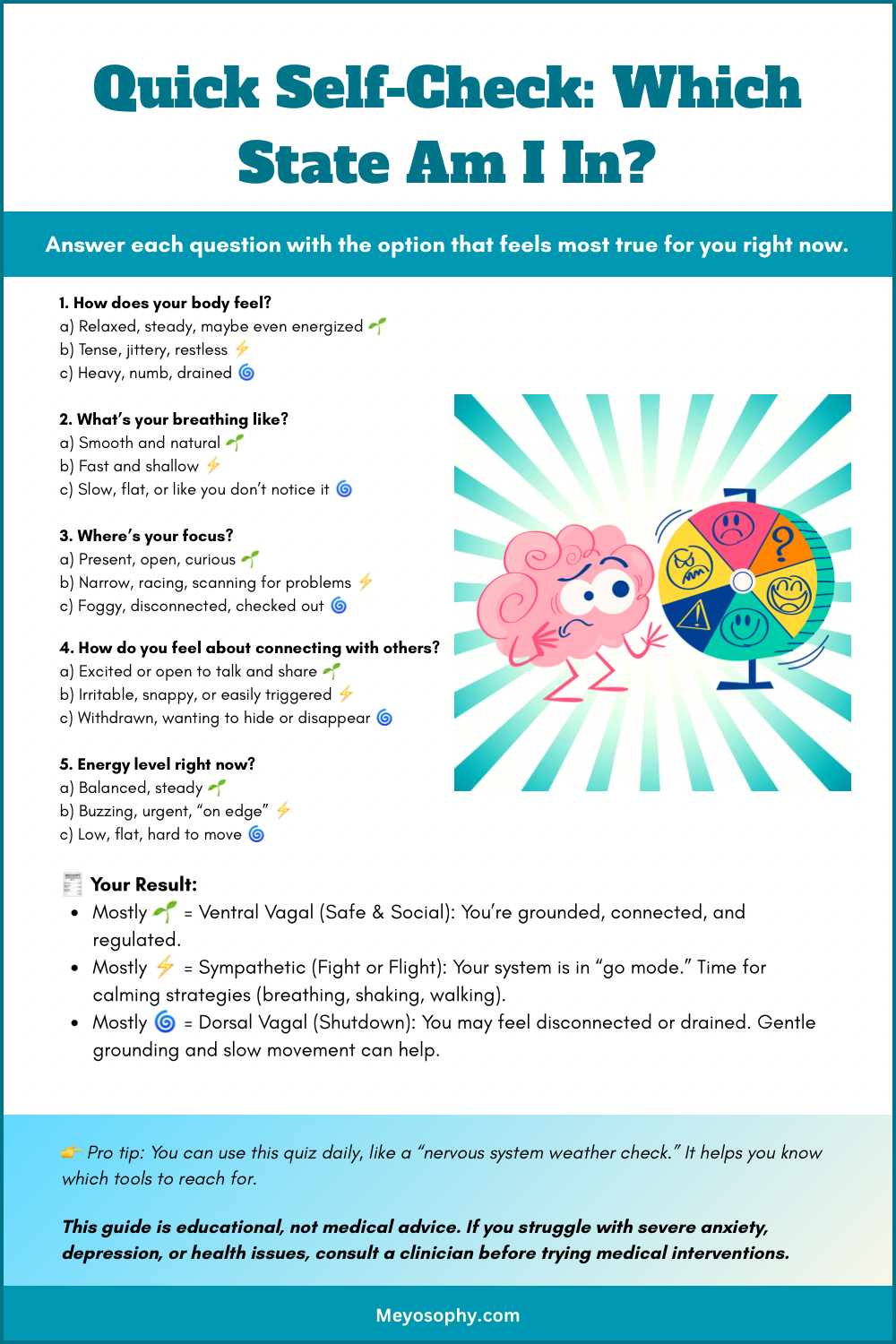

- 🌱 Ventral vagal (safe & social)

You feel grounded, open, curious. You have: an expressive face, warm voice, flexible thinking. - ⚡ Sympathetic (fight or flight)

Mobilizes for action. Heart races, breath quickens, muscles tense. It’s helpful short-term, exhausting if it’s stuck[^5]. - 🌀 Dorsal vagal (shutdown)

If escape feels impossible, your body “hits the brakes”. You feel: numb, disconnected, heavy. It’s an ancient survival strategy[^4].

These states aren’t “good” or “bad.” They’re adaptive. The problem comes when stress locks you into sympathetic overdrive or dorsal shutdown long after the danger is gone.

Why Vagal Tone Matters

Vagal tone = how flexible and responsive your vagus nerve is.

- High vagal tone → quicker stress recovery, better emotional balance.

- Low vagal tone → linked with anxiety, depression, and slower regulation[^6].

A practical way to measure this? Heart Rate Variability (HRV). Tiny beat-to-beat changes in your pulse. Higher HRV often means better parasympathetic balance[^7]. You can’t feel HRV, but smartwatches can measure it and you can train it with breathwork and biofeedback[^8].

The Vagus Nerve & Mental Health

- Anxiety: When fight-or-flight gets stuck “on,” the vagus can’t easily apply the brakes[^6]. This can cause anxious feelings.

- Depression: Shutdown states can mimic fatigue, numbness, and withdrawal[^4].

- Trauma/PTSD: The nervous system may be hypervigilant or freeze easily. Polyvagal-informed therapy uses cues of safety to restore balance[^4].

- Gut–brain link: Gut inflammation or microbiome changes can affect mood through vagal pathways (remember the upward and downward traffic) [^2][^3].

- Medical treatments: Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) shows promise for depression and epilepsy (more on this later)[^9].

Real-Life Examples of Polyvagal States

🌱 Ventral Vagal: Safe & Social

This is when you feel calm, grounded, and connected.

- You’re laughing with a friend over coffee and feel genuinely present in the moment.

- You finish a project and take a deep breath of relief, noticing your shoulders are relaxed.

- You’re playing with your pet and feel warm, content, and “here.”

Body clues: relaxed muscles, steady breath, warm chest, curious mind.

⚡ Sympathetic: Fight or Flight

This is when your system gears up for action, whether the “danger” is real or not.

- Your boss emails, “We need to talk,” and your heart jumps into your throat.

- You’re stuck in traffic, already late, and your jaw is clenched while you grip the steering wheel.

- Your child has a meltdown in the supermarket, and you suddenly feel hot, tense, and ready to either argue or flee the scene.

Body clues: racing heart, shallow breathing, sweaty palms, restless energy, tunnel vision.

🌀 Dorsal Vagal: Shutdown

This is when your body decides it’s too much and hits the brakes, a survival mode of “numb out.”

- You come home after a long, stressful week and collapse on the couch, staring at your phone for hours, unable to move.

- You’re in a social situation where you feel overwhelmed, and suddenly your brain goes foggy and words won’t come out.

- You feel like everything is “too much” and want to hide under the covers instead of facing the world.

Body clues: heavy body, low energy, flat voice, blank mind, desire to withdraw.

Moving Between States

⚡️ From Sympathetic → 🌱 Ventral Vagal

When you’re stuck in sympathetic activation, your body is in high alert: heart racing, shallow breath, muscles tense, mind scanning for danger. This is useful if you need to slam the brakes in traffic, but not so great when you’re just trying to sleep or enjoy dinner.

To return to the ventral vagal state (calm, safe, connected), the goal is to signal to your nervous system that the danger has passed. Think of it as helping your “inner guard dog” relax.

Ways to shift:

- Slow, extended exhale breathing → Try 4-6 breathing (inhale for 4, exhale for 6). A long exhale stimulates the vagus nerve and tells your body it’s safe.

- Grounding with your senses → Look around the room and name 5 things you see, 4 you feel, 3 you hear, 2 you smell, 1 you taste. This interrupts racing thoughts and pulls you back into the present.

- Safe social contact → Eye contact, a warm hug, or even talking kindly to yourself can activate ventral vagal pathways.

- Gentle movement → Walk slowly, stretch, or shake out tension. Moving energy helps discharge the “fight/flight” buildup.

🌀 From Dorsal → ⚡️ Sympathetic → 🌱 Ventral

When you’re in the dorsal vagal state, it can feel like hitting a brick wall: numb, frozen, foggy, disconnected, maybe even hopeless. Your system has decided, “I can’t fight or run, so I’ll shut down.”

The first step out of dorsal isn’t straight to calm. It’s usually through mobilization (sympathetic). Think of it as warming the engine before driving off.

Ways to shift:

- Gentle stimulation → Start with very small actions: wiggle your fingers, tap your feet, or stand up and stretch. The goal is to add just a little energy.

- Engage your senses → Splash cool water on your face, listen to upbeat music, or hold something textured (like a stone or fabric). This wakes up the nervous system without overwhelming it.

- Small goals → Do one simple, achievable task (make tea, fold one shirt). Success builds momentum and helps you climb out of shutdown.

- Rhythmic movement → Rocking, swaying, or walking at a steady pace can gently reintroduce movement and activate the sympathetic system in a safe way.

From there, once you’re mobilized and have a little more energy, you can use ventral practices (breathing, grounding, connection) to return to safety and social engagement.

The nervous system works in steps, not leaps. You don’t jump straight from freeze to calm: you usually move dorsal → sympathetic → ventral.

Tools to Strengthen Your Vagus Nerve

- Slow breathing (extended exhales)[^8].

- Cold exposure (splash face, end shower cool)[^10].

- Humming/singing (vibrates vagus near vocal cords)[^11].

- Safe social contact (ventral shortcut)[^4].

- Mindful movement (yoga, tai chi, walking)[^12][^13].

- HRV biofeedback (train your “vagal brake”)[^8]. This is best done with a professional.

- Play & laughter (yes, memes count)[^4].

- Gut & sleep basics (fiber, fermented foods, regular sleep)[^2][^3][^7].

Mini Vagus Toolkit (Quick Wins)

- 60-Second Downshift: Inhale 4, exhale 8 ×8 rounds. Hum on last exhale.

- Face Reset: Cool washcloth over eyes/ cheeks 60s → slow exhale → soften jaw.

- Walk & Breathe: Sync steps with 4-in, 6-out breath.

- Connection: Send one kind text/voice note.

The Gut–Brain–Vagus Loop

Stress can cause gut knots because the vagus nerve links digestion and mood. Inflammation or dysbiosis can worsen anxiety/depression and vice versa[^2][^3]. Supporting gut health + vagal tone helps both ends. So include fermented food and fibre to not only help your gut, but also your mood. It really is a two way street.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (Medical)

VNS is an FDA-approved treatment for epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression. It uses electrical impulses to the vagus via implants or ear devices. It’s promising, but strictly medical territory[^9]. The tools in this guide are behavioral ways to engage similar pathways. You can always ask your doctor about options like VNS.

Your 2-Week Vagus Reset

- Daily: Breathing practice (4-6 or resonance breathing).

- Daily (choose one): 10–20 minutes of mindful movement (walk, yoga, tai chi).

- Morning: 15-30 seconds cool face splash or cool shower finish.

- 3×/week: Sing out loud (shower karaoke counts) or hum for 3–5 minutes.

- Daily: One safe social connection (message, short chat, pet time).

- Always: Sleep + gut-friendly meals. Aim for consistent bed/wake times + fiber/fermented foods most days.

Track: Notice how quickly you “settle” after stress. That’s your vagus getting stronger.

Disclaimer

This guide is educational and not a substitute for medical care. If you have significant symptoms (e.g., severe anxiety/depression, fainting, heart/respiratory issues), or are interested in medical VNS, talk with a qualified clinician.

Conclusion: Why the Vagus Nerve Matters for Mental Health

The vagus nerve may seem like just another piece of anatomy, but it’s really the hidden thread weaving your body and mind together. It’s the messenger that tells your brain whether you’re safe, stressed, or shut down and it plays a key role in shaping how you feel, think, and connect with others.

When your vagus nerve is flexible and responsive, you can bounce back from stress more easily, settle into calm states, and feel grounded in your relationships. When it’s stuck or overwhelmed, you might notice more anxiety, burnout, or emotional disconnection.

The good news? You’re not powerless here. Simple practices can “tone” the vagus nerve, helping you shift out of fight, flight, or freeze and back into a state of safety and balance.

Understanding the vagus nerve is more than biology, it’s a roadmap for mental health. By learning to work with it, you gain tools to regulate your emotions, restore calm, and create the conditions for healing and growth. In my opinion it’s the missing link for a lot of people when it comes to their mental health.

Further reading

Want to read more about the Polyvagal Theory and Stephen Porges? You can do that here. Or if you want more resources about the Polyvagal Theory, the Vagus Nerve and further reading you can go to the website of the Polyvagal Institute.

Sources

[^1]: Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Vagus Nerve: What It Is, Function & Disorders.

[^2]: Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 49.

[^3]: Tracey, K. J. (2002). The inflammatory reflex. Nature, 420(6917), 853–859.

[^4]: Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory. W. W. Norton.

[^5]: Harvard Health Publishing. (2018). Understanding the stress response.

[^6]: Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 747–756.

[^7]: Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Heart rate variability and self-regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 213.

[^8]: Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000). Resonant frequency biofeedback training. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 25(3), 177–191.

[^9]: Nemeroff, C. B., et al. (2006). VNS therapy in treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 31(7), 1345–1355.

[^10]: Khurana, R. K., & Wu, R. (2006). The diving response: Physiology and clinical implications. Autonomic Neuroscience, 125(1–2), 66–81.

[^11]: Vickhoff, B., et al. (2013). Music structure determines heart rate variability of singers. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 334.

[^12]: Pascoe, M. C., & Bauer, I. E. (2015). Yoga’s effects on stress and HRV. International Journal of Yoga, 8(2), 76–86.

[^13]: Wang, C., et al. (2010). Tai Chi is effective in reducing depressive symptoms. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(1), 40–48.

Wow, I learned something new here! I didn’t realize the vagus nerve played such a big role in stress, mood, and even digestion. The idea of it being like a “calm button” makes it so much easier to understand. I especially like how Polyvagal Theory breaks down those different states—it really clicks. Now I’m curious to try out some of those tools to help strengthen vagal tone.

This was such an interesting read!

I had no idea it controlled so much of what we do and how our body’s function. Very interesting!

You did a ton of research for this article and it was really fascinating to read! The vagus nerve literally has a lot of nerve! 🤣 And it’s so interesting how our bodies and minds work in these ways. This was really helpful and informative! Loved how you explained everything in relatable terms and examples❤️

How fascinating!! I appreciate the insight and will definitely be trying the reset!

Very interesting article, and informative as well. I am a healthcare professional and we know how it is important to regulate.