If you’re depressed, looking into therapy is already a huge step. Therapy doesn’t “fix” people: it gives you tools, someone to practice with, and a clearer way forward. This guide explains the main types of therapy used for depression, what they actually do, and how to choose one that fits you.

Medical disclaimer: This post is for information only and is not medical advice. If you are in immediate danger or having suicidal thoughts, call emergency services or your local crisis line right now. For diagnosis and treatment that fits your situation, please see a licensed clinician. Read the full disclaimer here.

Why therapy can help

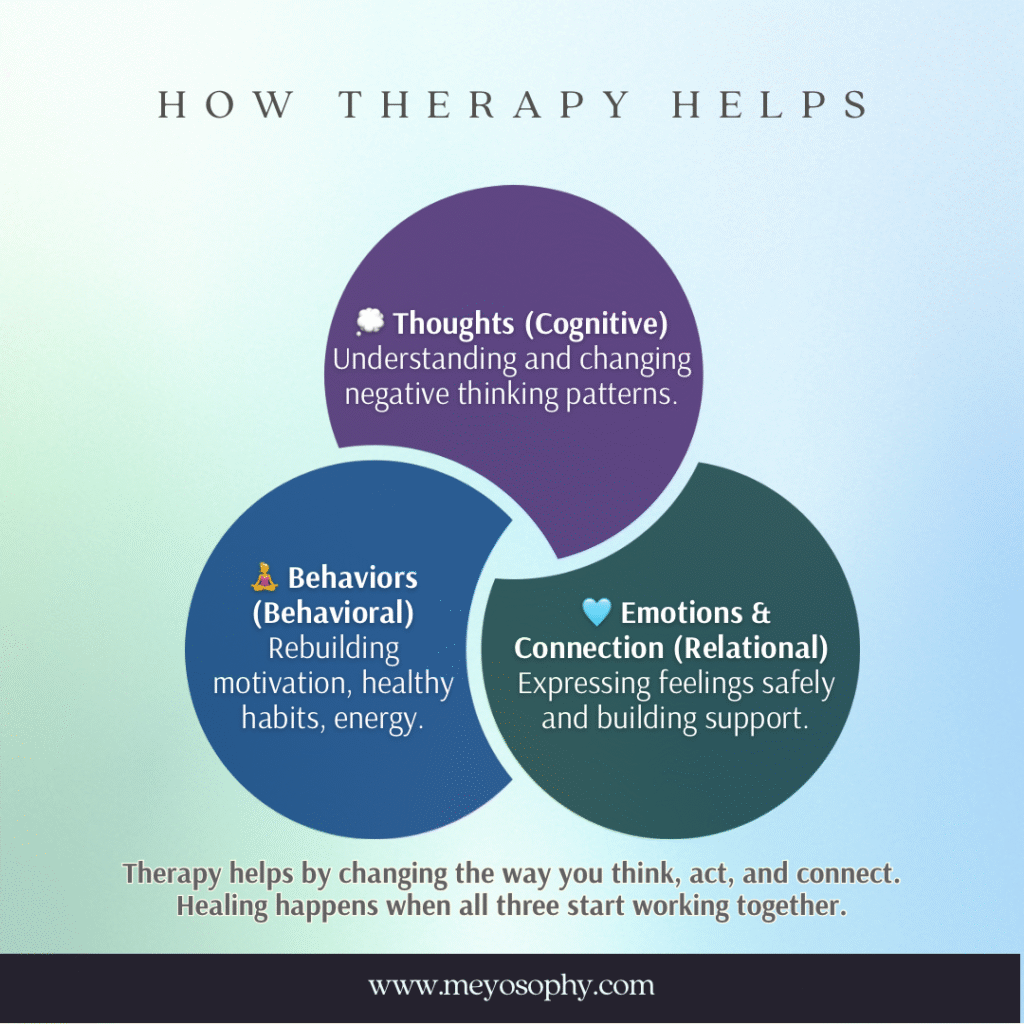

Depression tends to come from many places: thoughts that get stuck, habits that pull you down, past pain, and biological stuff in your brain. Therapy helps in three main ways: it teaches skills to change thinking and behaviour, it helps you process painful experiences, and it supports you while you practice new habits. Clinical guidelines around the world recommend talking therapies as a core treatment for depression. [1]

The main therapy types

Below are the therapies you’ll most often meet.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): “learnable skills to change how you think and act”

What it does: Helps you spot unhelpful thoughts (like “I’ll always fail”) and test them. Teaches small behaviour changes so you slowly feel better.

Why people like it: Structured, practical, and backed by lots of research. It often includes homework (short daily exercises). [2]

Read more about CBT here.

Behavioural Activation (BA): “action first”

What it does: When depression makes you stop doing things, BA asks you to schedule tiny, meaningful activities that pull you back into life.

Why people like it: Simple and direct. Mood often improves when activity increases. Research shows BA is as effective as more complex therapies for many people. [3]

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): “fix the relationship”

What it does: Focuses on how relationships, grief, or life changes (like becoming a parent) affect mood, and teaches practical ways to improve them.

Why people like it: Great if your depression links to loss, conflict, or big life transitions. [4]

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT): “notice your thoughts without fighting them”

What it does: Combines mindfulness practice with therapy skills to stop rumination, useful to prevent future episodes, especially if you’ve had depression before.

Why people like it: Helps you step back from negative thoughts instead of getting pulled in. MBCT can reduce relapse for people with recurrent depression. [5]

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT): “live your values, even with hard feelings”

What it does: Helps you accept uncomfortable feelings and commit to actions that matter to you. It’s less about changing thoughts and more about changing your relationship with them.

Why people like it: Helpful when fighting thoughts makes things worse. [6]

Want to try some ACT exercises? You can try some here.

Psychodynamic (short-term): “understand patterns from your past”

What it does: Looks at recurring patterns and how early relationships shape current feelings. Short-term versions are focused and goal-oriented.

Why people like it: Useful if you want to explore the roots of your mood rather than only symptom-change. Evidence supports benefit for depression. [7]

EMDR: “for trauma-linked depression”

What it does: Originally for PTSD, EMDR helps process traumatic memories that may be fueling depression.

Why people like it: If your depression is clearly tied to traumatic events, EMDR can reduce symptoms for some people. Evidence is growing. [8]

DBT: “skills for strong emotions and safety”

What it does: Teaches emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and relationship skills. Often used when self-harm or very strong emotional swings are present.

Why people like it: It’s structured and focused on safety, very useful when emotion regulation is a major issue. [9]

What about medication and “combined” treatment?

For moderate to severe depression, therapy plus medication often gives the best chance of recovery. Medication can reduce the fog enough that therapy becomes more effective. For mild depression, therapy alone (including guided self-help or low-intensity CBT) is often recommended first. Clinical guidelines suggest matching treatment to severity and personal preference. [1][10]

If several attempts don’t help, there are other medical treatments (rTMS, ECT, and esketamine in specialist settings). These are not first-line for most people but can be life-changing for treatment-resistant cases. They require specialist assessment. [11]

Different therapy settings

- One-on-one therapy (in person or online): most common and flexible.

- Group therapy: cheaper, good for skills practice and feeling less alone.

- Guided self-help / low-intensity (workbooks, online CBT with occasional coach support): great for milder depression or when access is limited. Guided online CBT has solid evidence when a therapist or coach supports it. [12]

- Apps: useful tools (mood trackers, breathing exercises), but they are best used alongside real therapy, not as replacements.

How to choose the right therapy / therapist (practical tips)

- Match the therapy to the problem. If avoidance dominates, BA; if trauma dominates, EMDR or trauma-focused CBT; if relationships are central, IPT.

- Ask about experience. Ask a therapist: “Have you treated people with depression before? Which therapy do you usually use?”

- Think logistics. Cost, session time, location, telehealth option, language. These matter more than you think.

- Trust matters. If you don’t click with a therapist after a few sessions, it’s okay to try someone else. The relationship is often the key ingredient. [1]

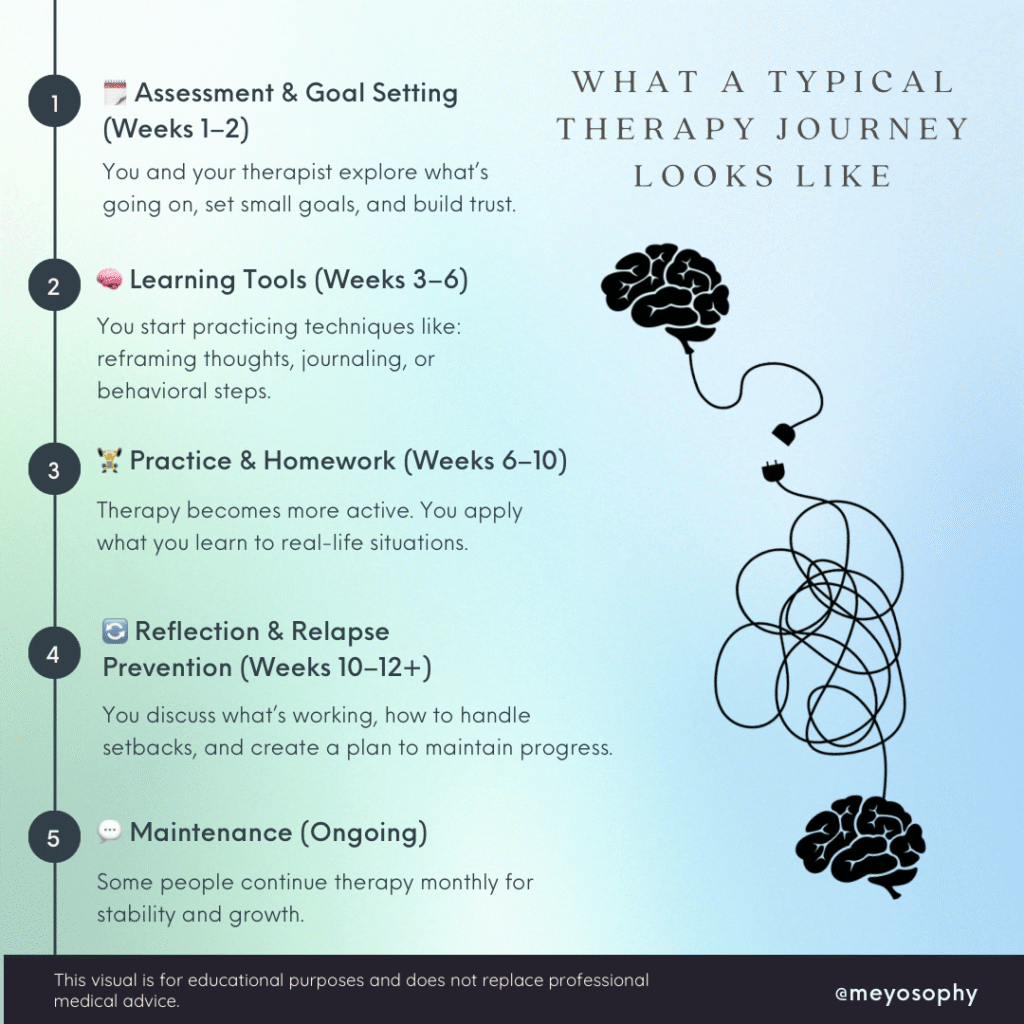

What a typical short course looks like

- First sessions: assessment, safety check (suicide risk), and a plan.

- Middle sessions: learn and practise skills (homework is common in CBT/BA).

- Later sessions: consolidate gains and make a relapse-prevention plan.

Many evidence-based programs run 8–20 sessions, but you can continue longer if needed. [2][3]

Simple Tools to Support Your Therapy

Healing doesn’t just happen in sessions, it also happens in the small choices you make between them. Try tracking your mood once or twice a day to notice patterns and small improvements. Schedule tiny, manageable activities (like a 5-minute walk or texting a friend); these help lift your energy and motivation over time. Use thought records to challenge negative thinking and remind yourself that thoughts aren’t facts.

When anxiety or panic hits, grounding and slow breathing can help you feel safer in your body. Pay attention to sleep and light too: going to bed and waking up at regular times supports mood stability. And finally, try a short mindfulness moment each day. Even a few minutes can help reduce overthinking and boost emotional balance.

Small steps matter. Pick one or two tools to start with and build from there. Progress often begins in the smallest routines.

Real-life tips for getting started (small, doable steps)

- Ask your GP for a referral or search local therapist directories.

- If cost is a problem, look for sliding-scale clinics, community mental health services, university training clinics, or guided online CBT programs. [12]

- Give a therapy a fair trial (often 6–12 sessions), but check progress. If nothing’s changing after a reasonable effort, discuss alternatives (new therapist, different approach, or medication). [1]

Final note: hope and patience

Therapy is not magic, it’s practice. Some weeks feel small; some weeks feel big. But many people recover or learn to live well with depression. Choosing to ask for help, learning new skills, and showing up (even when it’s hard) are meaningful steps forward. If you’re struggling, just know you can get better.

If you’re very unwell or thinking about suicide: If you have thoughts of harming yourself, a plan, or you can’t safely care for yourself reach out now. In the U.S., call or text 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline). In the U.K., Samaritans are 116 123. If you’re elsewhere, find local helplines at findahelpline.com. If you’re in immediate danger, call your local emergency number. These situations are medical emergencies, please seek urgent help. [11]

Sources

- NICE. Depression in adults: treatment and management (NG222). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- APA. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Depression Across Three Age Cohorts. American Psychological Association.

- Gautam M., et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression (meta-analysis/overview). PMC.

- Ekers D., et al. Behavioural Activation for Depression: meta-analysis. PLoS One / PubMed Central (2014).

- Kuyken W., et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for relapse prevention (review). PMC.

- APA guideline / ACT evidence summaries.

- Driessen E., et al. Short-term psychodynamic therapy for depression: meta-analysis. PubMed.

- Seok JW., et al. EMDR meta-analyses and reviews for depression. PMC review (2024).

- Linehan MM., et al. DBT evidence for emotional dysregulation and self-harm. PubMed.

- Internet-delivered CBT evidence: Karyotaki et al., JAMA Psychiatry (2021).

- rTMS / ECT / esketamine guidance and evidence summaries (NICE, clinical reviews, FDA updates).

- NICE guidance on stepped care, low-intensity interventions, and online CBT recommendations.