If things around you sometimes feel dreamlike, foggy, unreal, or “off,” and you’ve ever thought, “Am I losing my mind?”: this article is for you. Derealization and depersonalization are confusing and frightening when you don’t know what they are. But they’re also common reactions to stress, anxiety, sleep loss, or trauma and there are clear steps you can take to feel safer and more present.

Disclaimer: The content on this blog is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional mental health advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of a qualified mental health professional or other licensed healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding your mental health or a medical condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay seeking it because of something you have read here.

If you are in crisis, feeling unsafe, or thinking about harming yourself or others, please seek immediate help by contacting local emergency services, a suicide prevention hotline, or a trusted friend or family member. In the United States, you can call or text 988 or use webchat at 988lifeline.org. If you are outside the U.S., you can find international hotlines here: https://findahelpline.com.

The author(s) of this blog are not responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided.

Quick overview: the definitions

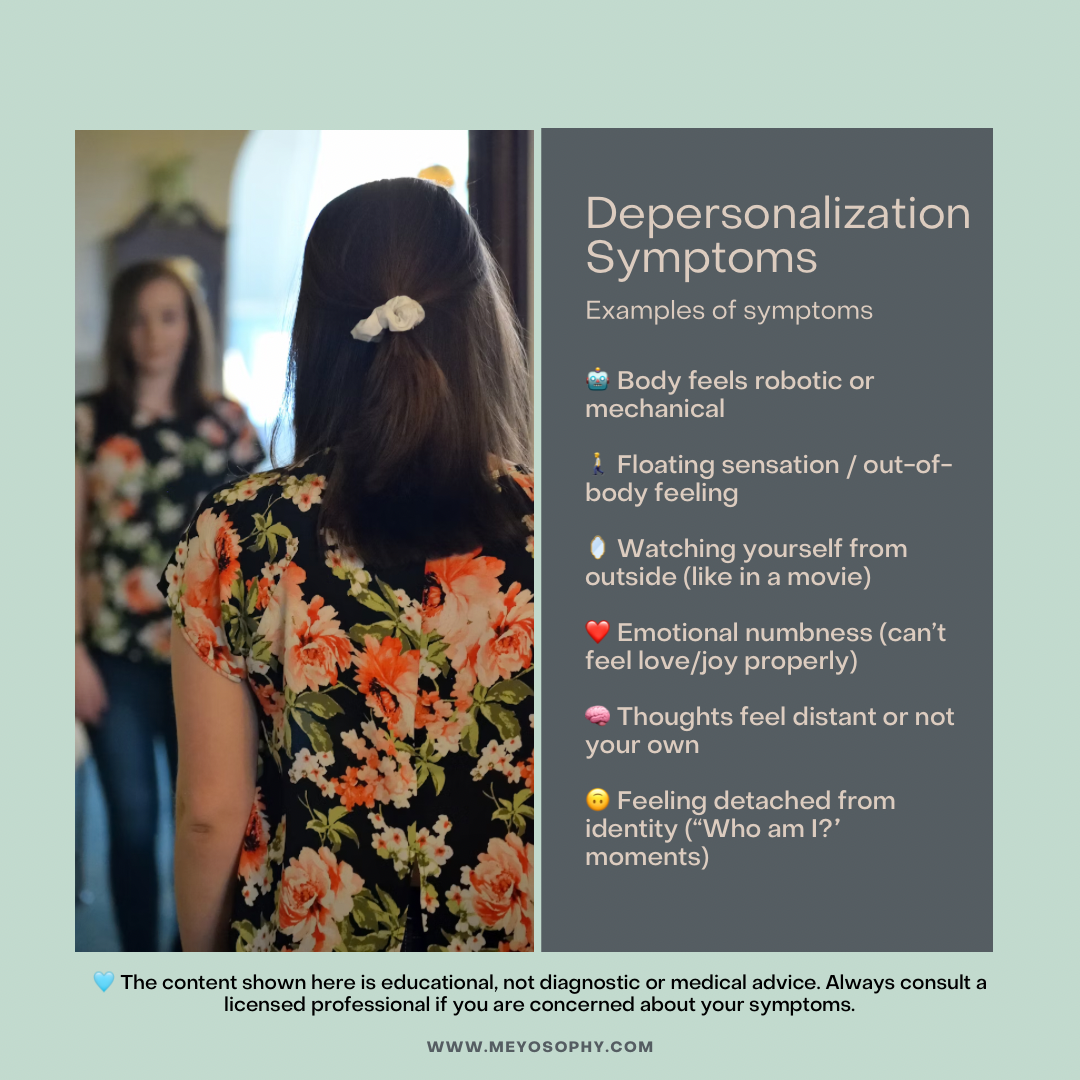

- Depersonalization (dp): feeling detached from yourself. People describe it as watching themselves from the outside, feeling as though their thoughts, body, or emotions belong to someone else, or feeling “robotic.”

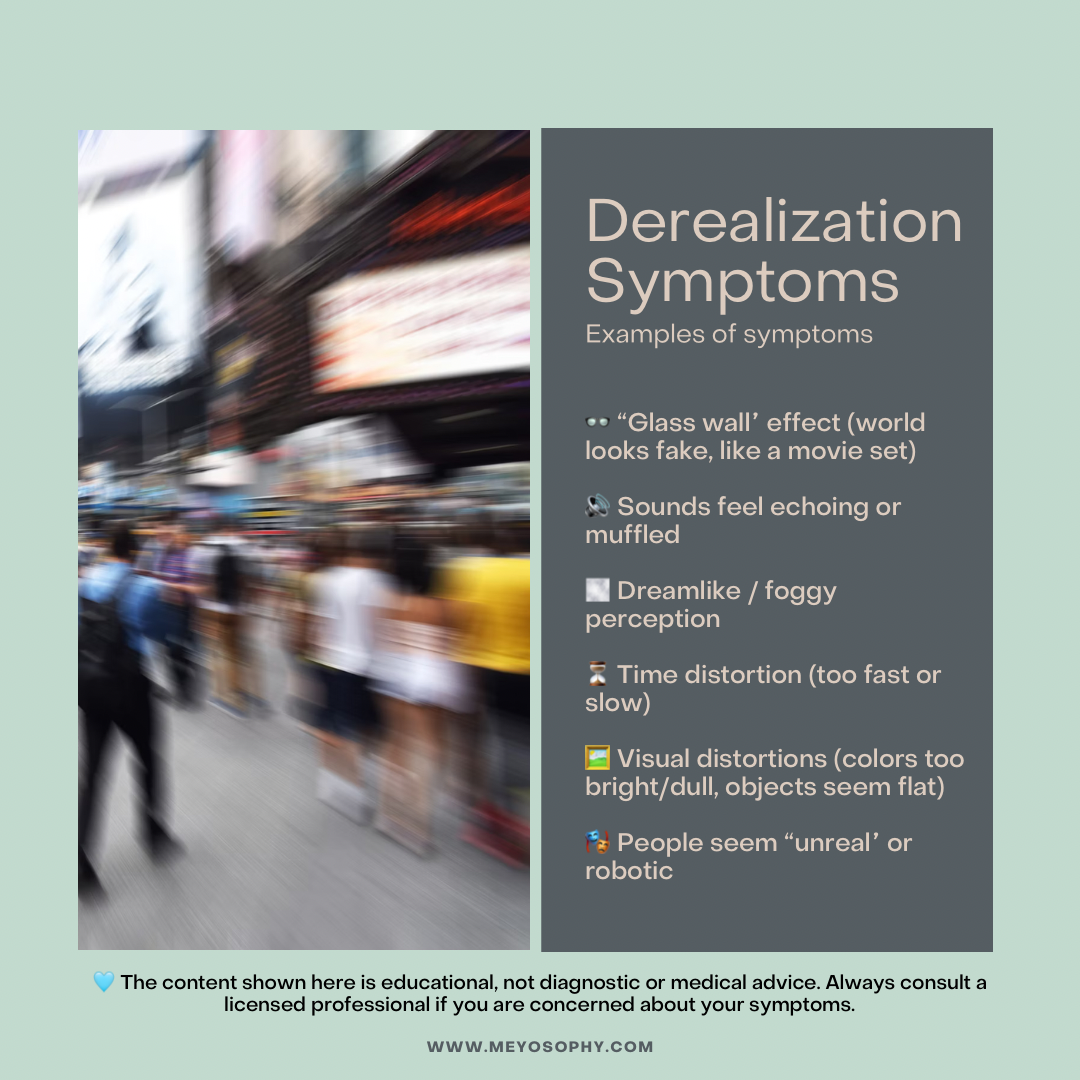

- Derealization (dr): feeling detached from the world. Things, people, or places may feel dreamlike, distant, flat, or visually distorted.

You can experience one or the other, or both together. When these sensations are brief and linked to a single stressful event (a panic attack, a sleepless night), they usually pass. When they’re persistent, very distressing, and interfere with daily life, clinicians may diagnose depersonalization–derealization disorder (DPDR). [1][2]

How common are DP/DR experiences?

Brief, passing episodes of derealization or depersonalization are surprisingly common. Population studies suggest that up to 50–60% of people experience at least one episode of DP/DR in their lifetime [7]. For most, it lasts only minutes or hours and doesn’t return. However, the persistent disorder, Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder (DPDR), is much less common, affecting about 1–2% of the general population at any given time [7][13]. Knowing you’re not alone in this can ease some of the isolation these experiences create.

How the DSM classifies it

In the DSM-5, DPDR is recognized as a dissociative disorder. The key criteria include:

- Intact reality testing (knowing that the altered perceptions are not actually true).

- Significant distress or impairment in functioning.

- Symptoms not due to substances, medical conditions, or other mental disorders [15].

This classification matters because it helps distinguish DPDR from psychosis and makes sure people receive appropriate care.

Why they feel so alarming (and why you’re not “going crazy”)

Two things make DP/DR especially frightening:

- The sensations feel unlike normal experiences, you may feel detached from your own body or like the world is unreal. That can trigger catastrophic thoughts like: “I’m losing my mind,” or “I’ll never be normal again.”

- The symptoms are unusual and hard to describe, so people who experience them often feel alone and misunderstood.

Here’s the important reassurance: most people who experience DP/DR retain reality testing, they know at some level the feelings are unusual and not actually true (for example, they know they aren’t literally living in a movie). That’s one key difference between DP/DR and psychosis. DP/DR is an extreme stress response or dissociative reaction, not a loss of contact with reality. [3]

Common triggers: what tends to set DP/DR off

DP/DR doesn’t usually appear out of nowhere. DP/DR can arise for several reasons. Panic attacks, trauma, chronic stress, and sleep deprivation are major triggers. But substance use also plays a role. Research shows that cannabis, hallucinogens, ketamine, MDMA, and alcohol withdrawal can provoke derealization and depersonalization, sometimes leading to persistent symptoms in vulnerable individuals [14]. Other contributors include sensory overload, neurological conditions, and certain medications. For many, it’s not one single cause but a combination of stressors that pushes the brain into this protective mode.

Most people notice it when one or several of these are present:

- Panic attacks or high anxiety. Panic can trigger intense depersonalization or derealization as the nervous system floods with stress hormones. [4]

- Trauma or PTSD. Dissociation is one way the brain protects itself during or after overwhelming events. [5]

- Sleep deprivation or exhaustion. Chronic tiredness makes sensory integration and emotion regulation harder.

- Sensory overload or overstimulation. Loud, crowded, or chaotic environments can push the nervous system into dissociation.

- Substances or withdrawal. Certain drugs (and their withdrawal) can provoke DP/DR-like states.

- Medical or neurological issues. Less commonly, medical conditions or medications can cause similar symptoms: medical causes should be checked and ruled out. [6]

Brief DP/DR experiences are fairly common; persistent DPDR as a disorder is less common but real and treatable. [7]

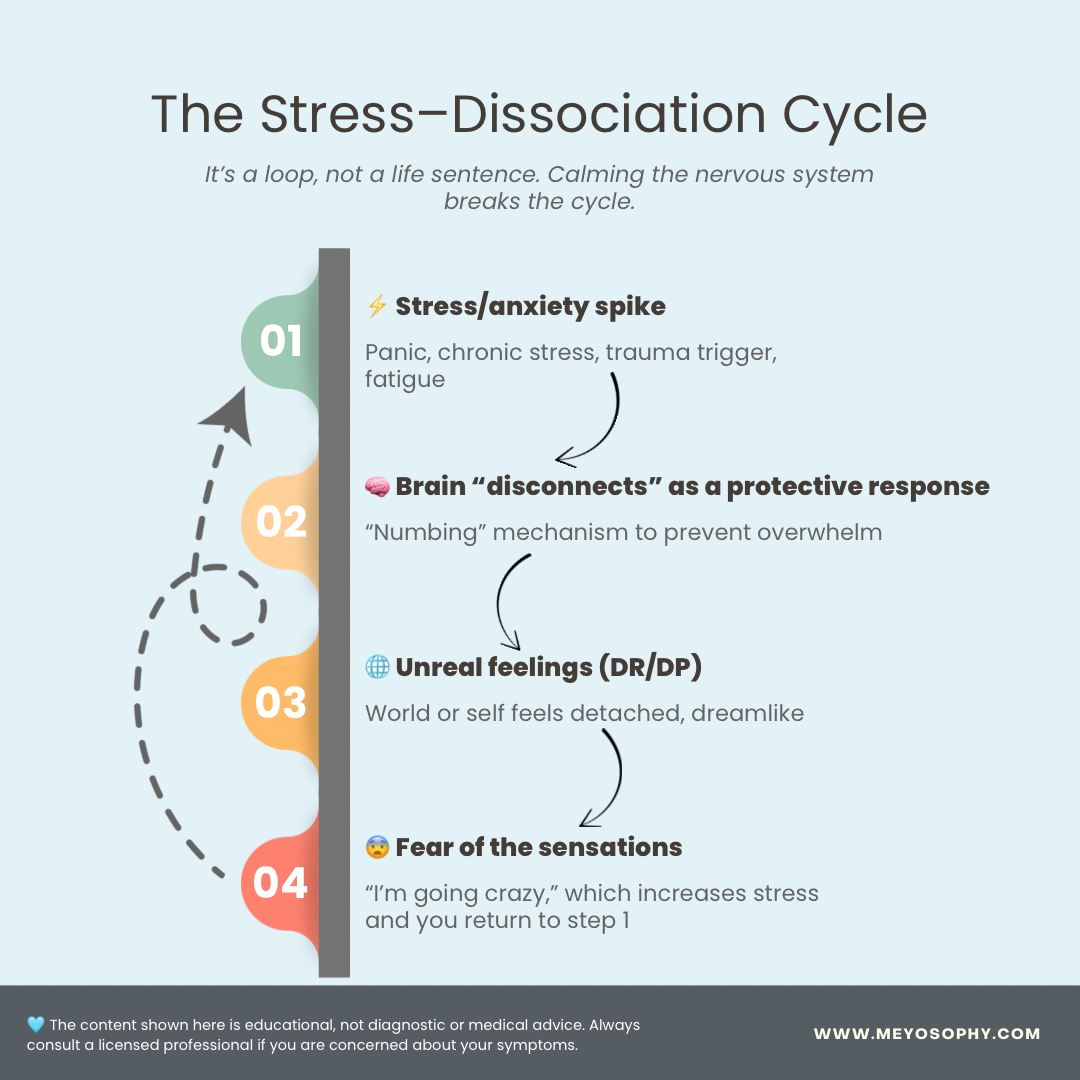

Why the brain does this (and why gentleness matters)

DP/DR is best understood as a protective brain response. When stress or danger feels overwhelming, the nervous system sometimes “disconnects” from emotions or surroundings to prevent overload. In the short term, this helps survival. But when the reaction gets “stuck,” it becomes distressing. That’s why being gentle with yourself is crucial. Your brain is already working in protection mode, pushing harder with self-criticism or fear often backfires, making symptoms worse. Calming the nervous system with grounding, rest, and compassionate self-talk helps create the safety the brain is searching for [3][5].

What’s happening inside your brain

Scientists don’t have all the answers yet, but current research suggests DP/DR involves changes in how the brain processes perception, emotion, and the “sense of self.” Brain imaging finds altered activity and connectivity in areas that help integrate sensory input with emotional response and self-awareness (for example, parts of the prefrontal cortex, insula, and anterior cingulate). That helps explain why things can look or feel muted, distant, or “numb.” [3][8]

Immediate tools: what to do right now when you feel detached

These techniques won’t magically remove every episode, but they can reduce distress and help you re-anchor in the present.

1) Quick grounding script: “5-4-3-2-1”

- Look around and name 5 things you can see (e.g., “a blue mug, a poster”).

- Name 4 things you can touch (e.g., “my jeans, the chair”).

- Name 3 things you can hear (e.g., “traffic, my breathing”).

- Name 2 things you can smell (or two scents you know).

- Name 1 thing you can taste (or take a small sip of water).

This sensory focus interrupts the dissociation loop and pulls attention into the here-and-now. (Practice it somewhere calm so it’s easier to use when you’re distressed.) [9]

2) An anchoring phrase to say out loud

Try: “This is derealization / depersonalization. It’s uncomfortable, but it can’t hurt me. It will pass.” Saying it out loud helps dampen catastrophic thoughts.

3) Ground physically

Plant your feet on the floor and press down for five slow breaths; hold a cold drink, touch something textured, or press your fingertips together. Clear physical sensations help your brain reconnect with the body.

4) Breathe with a focus on longer exhales

Inhale for ~4 seconds, pause briefly, exhale for ~6–7 seconds. Longer exhales stimulate the parasympathetic system and lower alarm signals that fuel dissociation.

5) Move gently

March on the spot, walk slowly, or do a short sequence of stretches. Movement supplies proprioceptive information (where your body is in space) that reduces “floating” sensations.

Combine steps 1–3 if you can: sensory anchor, grounding touch, and an anchoring phrase. Those three together often work well. [9][4]

Longer-term treatment approaches that help

If DP/DR is ongoing or interfering with life, evidence points to psychotherapy as the main effective route, with some promising results for specific CBT approaches.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for DP/DR

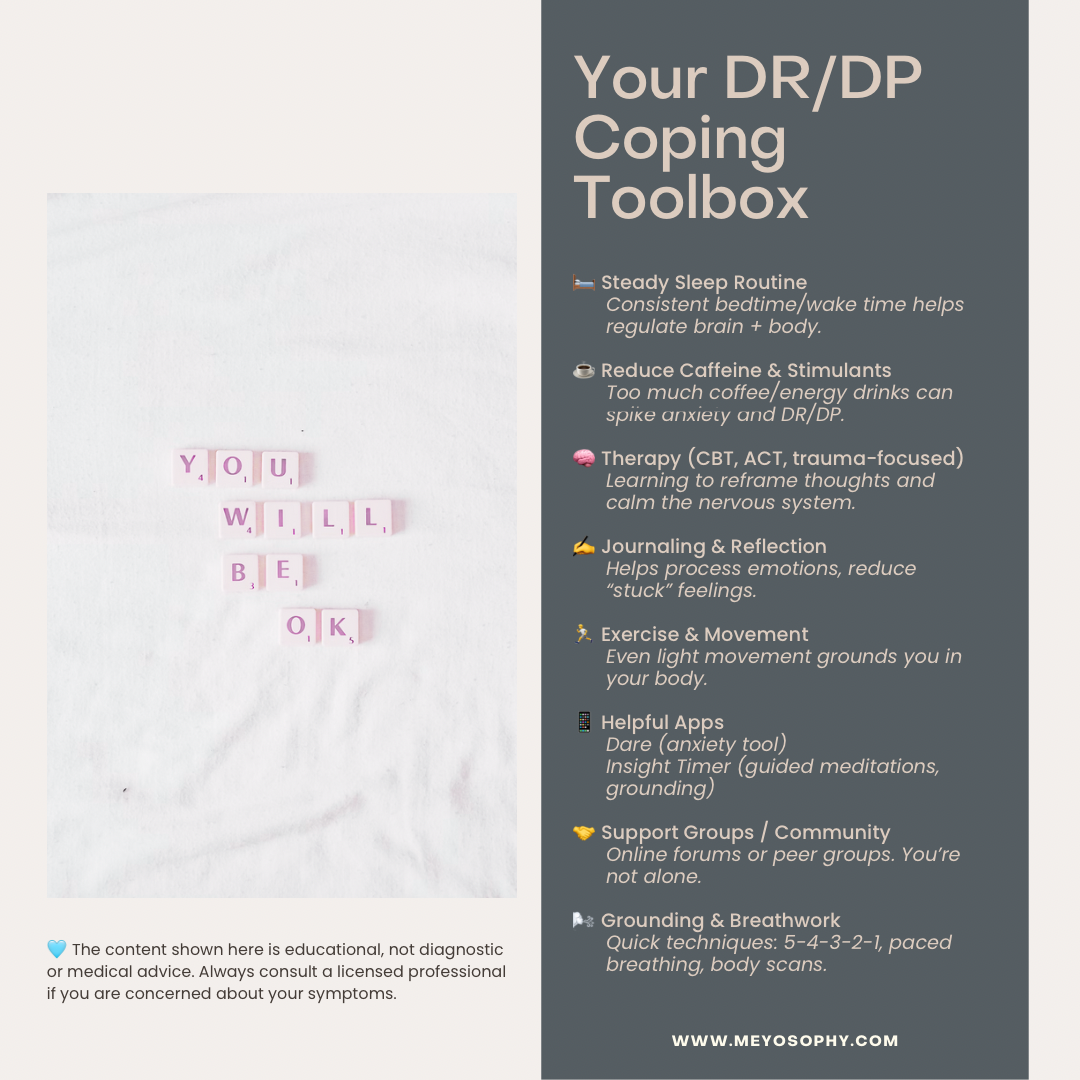

CBT adapted for DP/DR (sometimes called CBT-f or CBT for depersonalization/derealization) focuses on changing catastrophic thoughts (e.g., “I’m going insane”), testing feared predictions, and reducing avoidance or safety behaviours. Small trial studies show CBT can reduce symptom severity and improve functioning; larger trials are underway. [5][10]

Grounding, DBT & skills training

Skills drawn from Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), especially distress tolerance and grounding exercises, are widely used clinically and can help people ride through episodes without increasing panic. [9]

Trauma-focused therapies (if trauma is a trigger)

If DP/DR is related to past trauma, trauma-focused therapies (EMDR, trauma-informed CBT) can be helpful, usually after stabilization and grounding skills are in place. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based approaches (e.g., ACT) can also help you change how you relate to dissociative sensations rather than trying to eliminate them. [5][11]

Medication

There is currently no medication specifically approved for DP/DR. Clinicians may prescribe antidepressants (SSRIs) or other meds for co-occurring depression or anxiety; these sometimes reduce DP/DR symptoms indirectly. Medication is usually an adjunct to therapy, not a stand-alone fix. Always discuss risks and benefits with a prescriber. [6]

Day-to-day adjustments that reduce episodes

Small, consistent lifestyle changes can lower the baseline nervous-system reactivity that makes DP/DR more likely:

- Sleep: Prioritize a stable sleep schedule. Poor sleep often worsens dissociation.

- Limit stimulants: Cut down on caffeine and recreational drugs that can spike anxiety.

- Stimulation: If crowds, screens, or noise trigger you, create quiet time frames in your day.

- Movement & grounding: Daily gentle exercise (walks, yoga) and short grounding practices help.

- Social connection: Spending time with safe people reduces isolation and anchors you.

- Track patterns: Keep a simple log (time, sleep, food, what you were doing) to spot triggers. [7]

How clinicians diagnose and what to expect at your first appointment

If you decide to see a professional, the assessment will usually:

- Ask about the symptoms (what you feel, when it started, how long episodes last).

- Check for medical causes that can mimic DP/DR (neurological issues, medications, substances).

- Explore mental health history (anxiety, PTSD, depression) and life stressors.

- Discuss impact on daily life and immediate safety.

Bring notes. A brief template you can copy to an appointment:

- “I feel detached from myself / the world X times per week. It started Y months ago. It follows panic / lack of sleep / a specific event. It feels like (describe). I’m worried because (impact).”

This helps clinicians understand your experience quickly. [6][10]

What recovery usually looks like

Recovery is often gradual:

- Episodes may become shorter and less frequent.

- Catastrophic thoughts subside with thought reframing.

- Functioning improves even if occasional DP/DR remains.

Some people fully recover; others learn to manage symptoms so they don’t control life. Research and clinical experience both show DP/DR is treatable, there are effective paths forward. [2][5]

When to seek urgent help

Go to emergency services or contact crisis lines if you experience:

- New chest pain, fainting, severe neurological symptoms (to rule out medical causes).

- Suicidal thoughts or plans, call emergency services or a crisis hotline immediately.

- Severe inability to function or prolonged dissociation with self-harm risk.

DP/DR itself is not usually a medical emergency, but the distress can be, and you deserve immediate support when needed. [6]

A personal note

I first experienced depersonalization and derealization after a panic attack seven years ago. For almost two years, I didn’t know what it was. That not-knowing sparked more anxiety and a deep sense of loneliness. When I finally learned about DP/DR and understood that it was a recognized stress response, not “going crazy,” I started to find relief. Learning how to respond (grounding, breathing, reminding myself “this is temporary”) made a big difference. Even now, it still lingers sometimes, but it’s far less intense. If you’re at the start of this journey, know that things can get better, and knowledge itself is a powerful first step.

Resources & Support

If you’re struggling with derealization or depersonalization, please remember you’re not alone. Many people experience these sensations, and support is available. Here are some trusted resources you can turn to for more information, grounding tools, or direct help:

📖 Professional Information

- NHS – Dissociative Disorders: Clear overview of symptoms, causes, and treatments. Visit NHS

- Mayo Clinic – Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder: Medical perspective on DP/DR. Visit Mayo Clinic

- Cleveland Clinic – DP/DR Overview: Easy-to-read explanation with diagnosis and treatment options. Visit Cleveland Clinic

📞 Crisis & Immediate Support

If DP/DR or anxiety ever feels overwhelming or unsafe, please reach out:

- United States: Call or text 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline)

- United Kingdom & ROI: Call 116 123 (Samaritans)

- International Crisis Text Line: Text HELLO to 741741 (US) or find international numbers at Crisis Text Line

🤝 Peer & Community Support

- No More Panic Forum: Visit Forum – active community around panic, anxiety, and DP/DR.

- Reddit – r/dpdr: Join here – lived experiences and coping discussions (note: not moderated by professionals).

- Online Support Groups: Look for moderated Discord or Facebook groups on DPDR for real-time peer connection.

🛠️ Self-Help Tools & Apps

- Psychology Tools – Free Grounding Exercises: Explore techniques

- Anxiety Canada: Visit Site – CBT-based strategies for anxiety and dissociation.

- DARE App: Get the app – practical tools for anxiety and panic (including DP/DR support).

FAQ

Most people retain reality testing and do not lose touch with reality. With treatment and self-care, many improve significantly. [3]

No. In DP/DR people usually know the experience is unusual and that their perception is altered, they do not believe hallucinations or delusions as reality. [3]

There’s no single “DP/DR pill.” Medication may help when co-occurring depression or anxiety is present, but therapy and skills are central. [6]

Final note: you’re allowed to be gentle with yourself

DP/DR is an understandably scary experience. If you’re reading this, that first step learning what it is and how to respond, is already progress. Try one grounding technique now. If the symptoms persist or interfere with life, please reach out to a clinician; help exists, and many people find relief with the right combination of skills, therapy, and support.

Sources

- NHS: Dissociative disorders (including depersonalisation and derealisation). NHS.uk.

- Wilkhoo HS, Islam AW, Reji F, et al. Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder: Etiological Mechanism, Diagnosis and Management. Discoveries / PubMed Central, 2024.

- Murphy RJ, Medford N, Gawronski K, Hunter MD. Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder and Neural Correlates of Dissociation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023.

- Mayo Clinic: Depersonalization-derealization disorder: Symptoms & causes. MayoClinic.org.

- McRedmond G, et al. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Depersonalisation–Derealisation Disorder (CBT-f-DDD) study protocol and evidence summaries. UCL / PLOS, 2024.

- MSD Manuals / Cleveland Clinic: Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder (DDDR): diagnosis and treatment considerations.

- Yang J, et al. The Prevalence of Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder: A Systematic Review. PubMed (2023).

- Sierra M, David AS. Depersonalization: Neurobiological perspectives. Biological Psychiatry. 2011.

- Psychology Tools: Grounding techniques (5-4-3-2-1). psychologytools.com.

- Farrelly S, et al. A brief CBT intervention for depersonalisation/derealisation (feasibility RCT). BMC/PubMed Central (2016/2024 updates).

- Reviews on trauma-focused approaches and ACT in dissociation: see literature summaries and clinical guidelines.

- Transdiagnostic DPDR treatment target review (systematic reviews, 2024).

- Michal M, et al. Prevalence of depersonalization and derealization in the general population. Psychol Med. 2009.

- Medford N, Sierra M, Baker D, et al. Cannabis and depersonalization: Neurobiology and risk. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010.

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Edition. 2013.